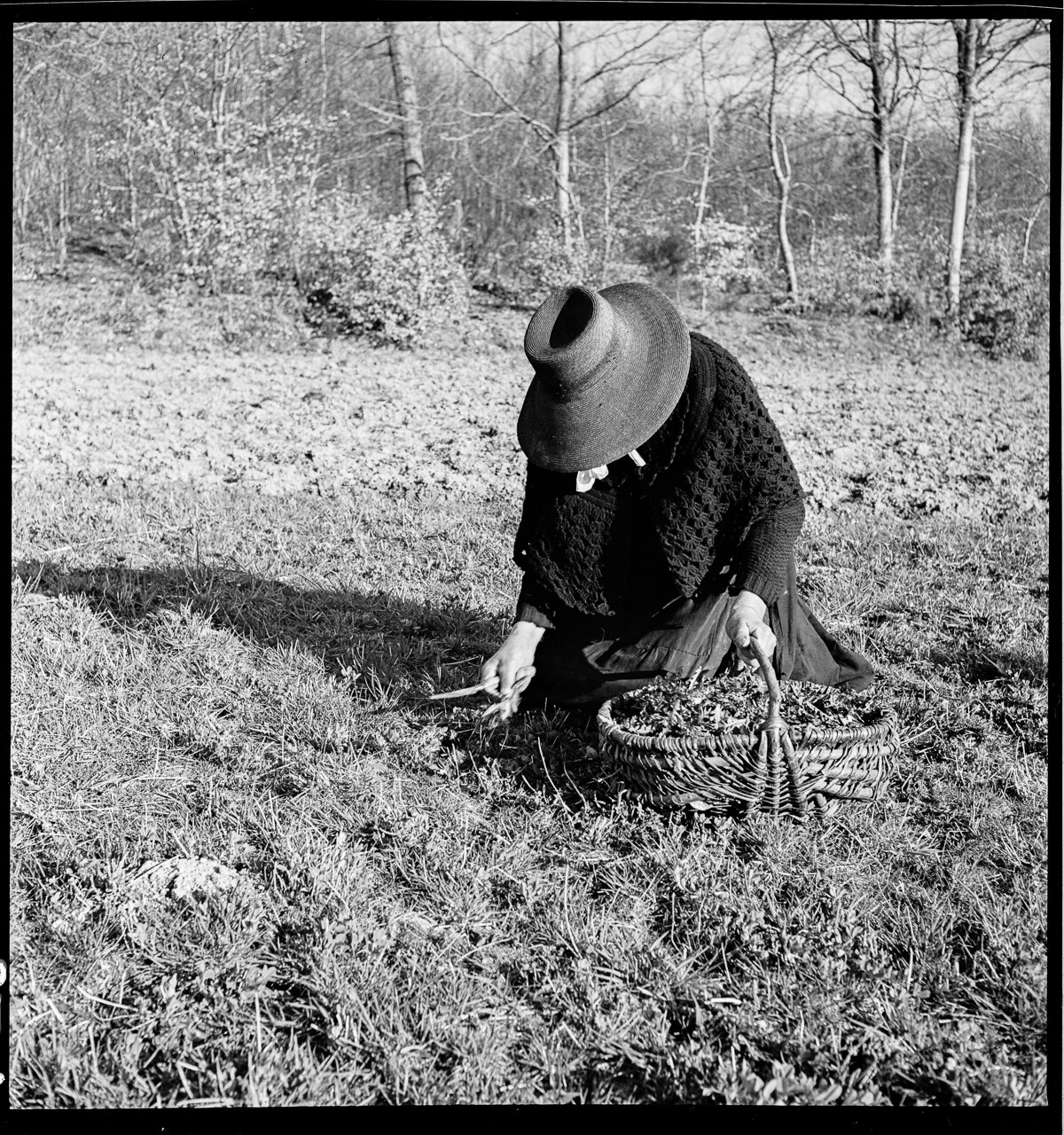

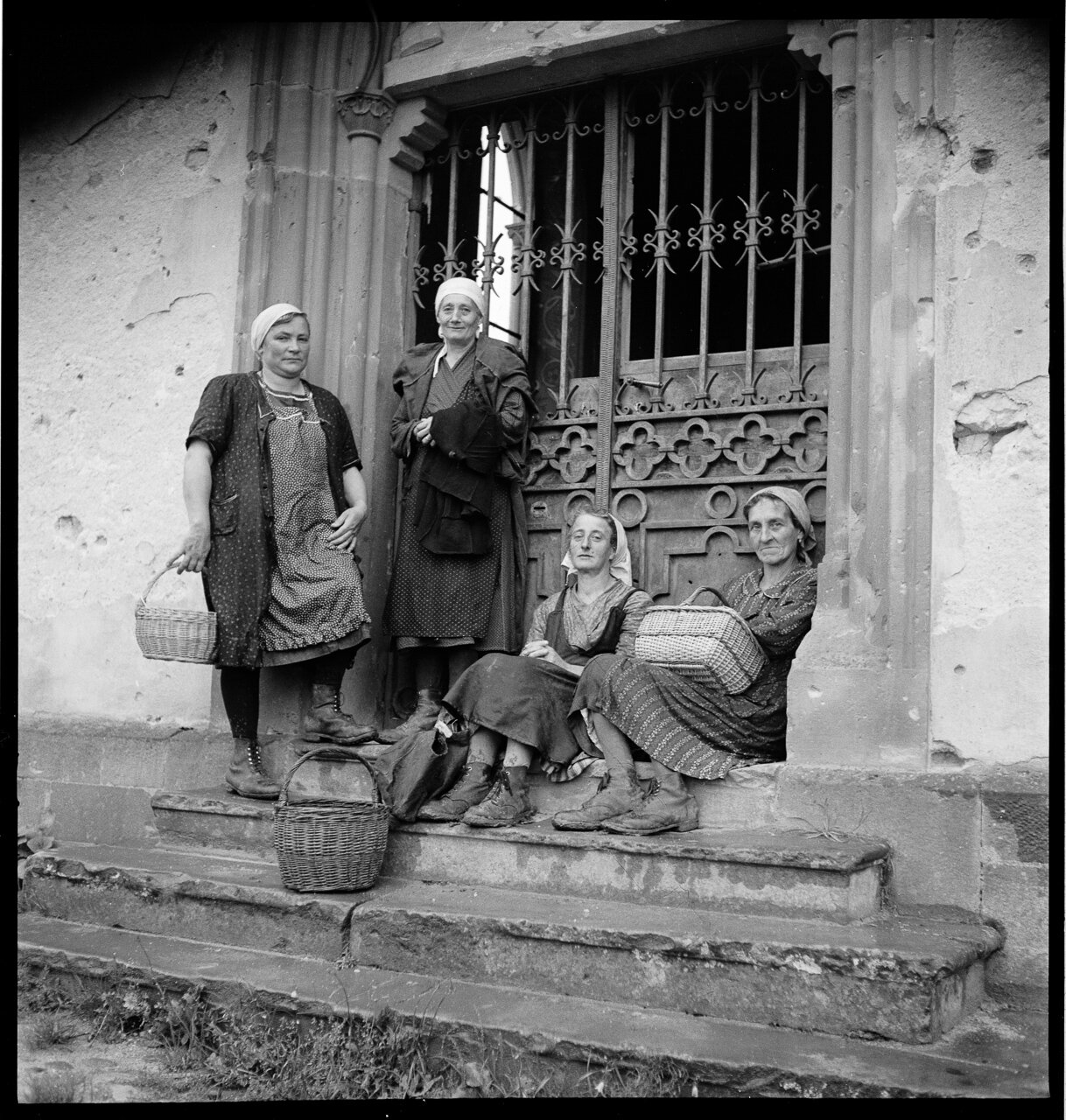

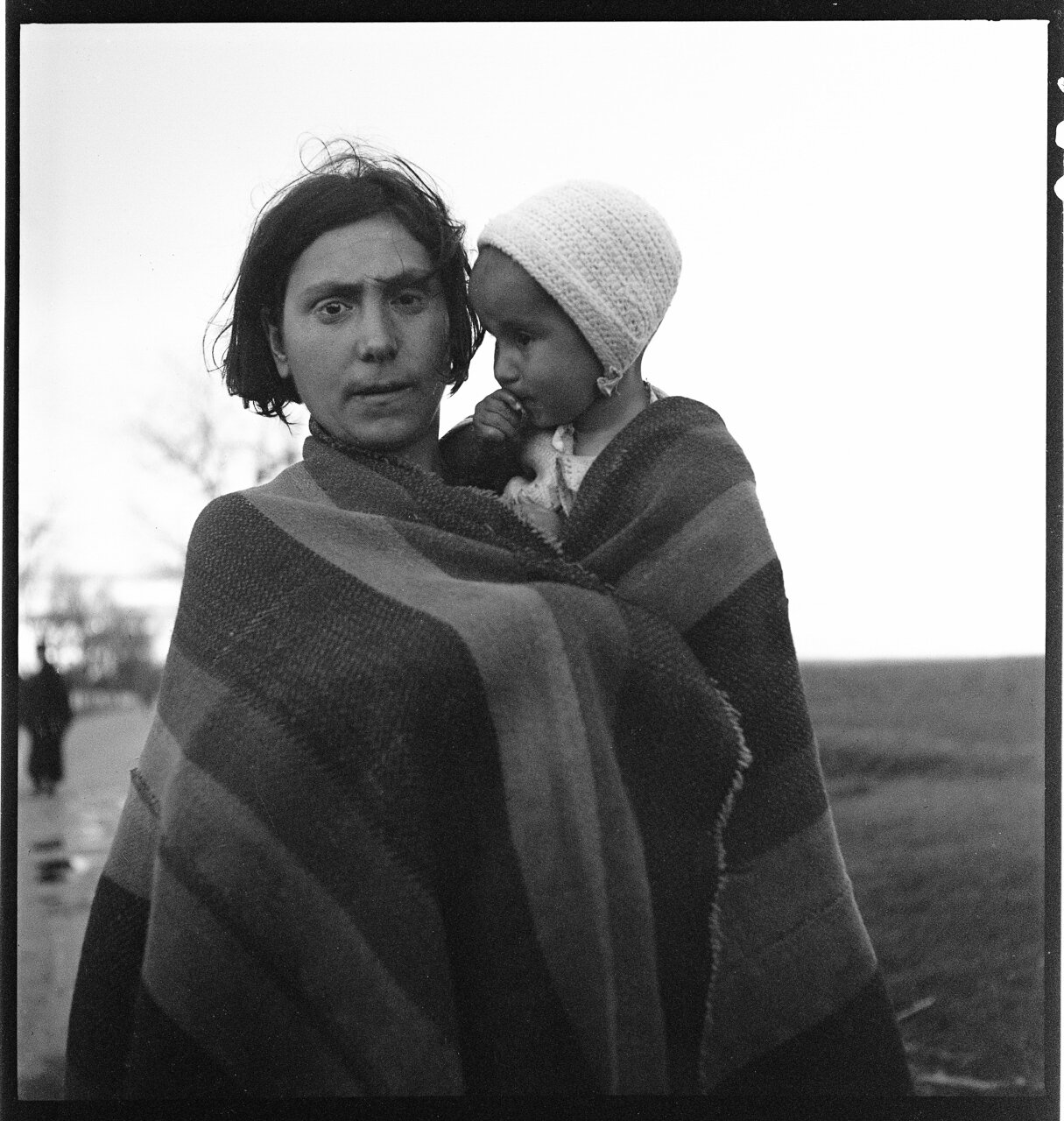

The Thérèse Bonney photograph collection at The Bancroft Library consists chiefly of documentary photographs taken throughout Western Europe during World War II. Bonney (UC Berkeley class of 1916) photographed all aspects of the war, but focused on its effects on the civilian population.

An active humanitarian, Bonney frequently used universal symbols in her work, allowing her images to speak beyond language barriers and leading their viewers to see beyond cultural differences. Her photographs of children were exhibited and published widely, influencing audiences to contribute to relief efforts for innocent victims of war. But the images throughout her archive feature another prominent symbol — women. Old women, young women, mothers, sisters, friends, neighbors; always at work, usually together, forever the epitome of personal sacrifice for the greater good. In honor of Women’s History Month, the Bancroft Library’s Pictorial Unit presents this collection of newly digitized images from the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection. The Finding Aid to the Thérèse Bonney Photograph Collection circa 1850-circa 1955 is available through the Online Archive of California. (Full article available here: UC Berkeley Library Update)